Now and then, I interview individuals who are doing something interesting, inspiring, and entrepreneurial – whether they are pursuing a particular interest, starting a non-profit or business venture, or somehow paved their own way to personal success and happiness. We can all learn from one another on how to better become leaders in our own lives, and I hope you find these conversations as inspirational as I do…

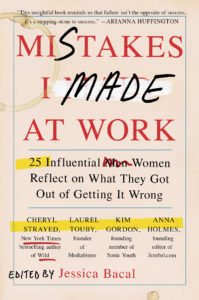

This week, my Q&A is with Jessica Bacal, whose new book, Mistakes I Made At Work: 25 Influential Women Reflect on What They Got Out of Getting it Wrong, just came out on April 30 (congrats!) and has been named Publishers Weekly’s “Top 10 Business and Economics Books for Spring” and in Fast Company’s “10 New Books You Need to Read This Year.”

This week, my Q&A is with Jessica Bacal, whose new book, Mistakes I Made At Work: 25 Influential Women Reflect on What They Got Out of Getting it Wrong, just came out on April 30 (congrats!) and has been named Publishers Weekly’s “Top 10 Business and Economics Books for Spring” and in Fast Company’s “10 New Books You Need to Read This Year.”

Jess and I briefly met in Washington DC through AAUW, and her work at Smith College as the director of the Wurtele Center for Work and Life helps promote positive purpose in the lives of our future generations of young women leaders. She sent me a copy of the book, and I opened it on a Saturday night expecting to peruse a few pages – and I was quickly hooked. HOOKED. She is a terrific interviewer, and the women she interviews – including Carol Dweck, Courtney Sullivan, Kim Gordon and Ruth Reichl – all have interesting perspectives that make you think and reflect. I truly enjoyed the book, and hope you get a chance to read as well – whether you are just starting your career or somewhere down the line, this book is well worth the time and I highly recommend (and seriously, so does PUBLISHER’S WEEKLY and FAST COMPANY, so clearly, it’s a winner)…

Thanks Jess, for the thoughtful Q&A!! Congrats with your huge success with this book…

Q: What inspired you to write this book?

As I was creating a new integrative leadership center for Smith students, I’d go to leadership conferences where panels of high-achieving women were often asked the question: “Could you talk about a mistakes and what you’ve learned from it?” The thing was, they rarely told stories that actually made them vulnerable. It’s really hard to come up with those kinds of stories when you’re on the spot, and so instead they’d express generalities, like “Learning from mistakes is so important.” I kept thinking: I’d like to hear actual stories, and to hear about how these women were able to succeed even though they’d made real mistakes.

This was partly because I was doing plenty of things wrong in my new role as director of the Wurtele Center for Work & Life – and partly because I saw the way students responded to true stories when they were shared. Our students are part of a generation of young women encouraged to “lean in” and take risks, but at the same time, they are often grappling with incredible pressure to be perfect. So I felt like there was a missing piece of the conversation. Taking risks at work means making mistakes, often big ones. I wanted to ask successful women to model imperfection by telling stories to demonstrate how screwing up and learning from it actually helped them to succeed.

Q: In my life, I’ve always tried to work with under the assumption that there really are no mistakes, and each opportunity is a chance to learn and grow in some way. But, you make a very important point about how the idea of “learning from your mistakes” ties into the good girl and perfectionist culture. Can you explain how you make that correlation and what we can do to overcome the perfectionist trap?

I agree – mistakes are opportunities to learn and grow. The connection I made to “good girl culture” is that when we just offer young people the advice to “learn from mistakes” – without sharing any of our own – then that advice can seem empty, like we’re just telling them one more way to do things right. However, when we’re willing to open up and be vulnerable, to say, “Look, I’ve screwed things up too – BIG time. Here’s how . . .” then it feels a little more real. Our advice becomes more resonant.

Q: I loved your reference to Daniel Goleman’s work and the idea that “Successful people are able to say to themselves, ‘While I may have screwed up, it doesn’t mean that I am a screw up.” Why do you think teen girls and women in particular can have a more difficult time making that distinction?

I’m hesitant to make distinctions like, “boys are this way, girls are that way,” because I know that boys and men can also be hard on themselves. But there’s some research that points to women being more ruminative than men – more likely to turn something over and over again in their minds, especially when that “something” is not good. And I think young women are raised in a culture that expects them handle themselves with polish and poise, to earn good grades AND to be involved in activities outside of school AND to be attractive and sexy. There was a great article about this in the NY Times a while back: “For Girls, It’s Be Yourself and Be Perfect, Too.” So I think young women may be more likely to see mistakes as being about their character – but again, boys and men are not immune to this.

Q: You describe the notion of a “glass cliff,” where women are more likely to receive criticism for mistakes, especially in male-dominated roles, and women of color are particularly susceptible to being seen as incompetent after making mistakes. It seems to me that fear of receiving such “flack” could be increasing anxiety among adolescents and young women. What do you think we can we do to build more awareness and change this cultural norm?

Ideally, every school and business should work to build a growth mindset culture in which mistakes are valued as learning moments. And I think people are beginning to see the use of reflecting on – rather than burying – mistakes: There’s a new Journal of Errology, started in 2012, which calls itself a “repository to publish all your unpublished trials & errors, futile hypotheses, shortfalls, false starts (and goes on from there).” A TED talk called “Doctors Make Mistakes” has been shared nearly a million times. And young entrepreneurs talk more openly than perhaps any other group about the importance of learning from mistakes. But wouldn’t it be great if high schools held “Fail Offs,” in which students and teachers got up and told their best failure stories – this idea is from Echoing Green’s fabulous Work on Purpose Curriculum. Or if displays in school hallways showed successive drafts of papers, and students’ reflections on those drafts – instead of just the final products?

Q: You interviewed such a wonderfully diverse group of women. How did you choose who to interview, and what was something surprising that came out of the interview process for you?

I had to really find the right people, women who “got” the value of mentoring by telling complex stories about work. There were plenty of people who said no; there were people who said yes and then changed their minds. But the final group of contributors are deep, thoughtful, reflective people who are interested in changing the cultural conversation, in making room for discussions about what we learn from the moments that didn’t go as planned. Hm . . . something surprising is that I became a lot more brave. I was nervous before every interview, but slowly got used to initiating conversations with women who were impressive and slightly intimidating to me. I started taking more risks at work, too – for example, applying for grants that I may not have applied for a year earlier. I was inspired by talking to these women who had taken risks in their careers.

Q: The section on “Taking Charge of Your Own Narrative” describes how women have recognized their strengths and become more purposeful. Can you describe a way that you have recognized your own personal strengths and become more purposeful in your own life?

I’ve come to realize that my writing background is a strength. All of the time I spent alone in a room, working on short stories – many of which were never published –informs what I do now. This is because I understand how useful specificity is, and how hard it is to get there as a writer. So when I work with students, inviting them to reflect on and write about their experiences at college, I use my background to guide them in doing specific writing. And when I developed this book, my interest was in specific stories rather than general advice. I’m only now starting to see the thread that connects the many parts of my working life, and seeing it is helping me to follow it – to become more purposeful and outspoken about my interest in narrative as a tool.

Q: I’ve loved the stories – and particularly the way you’ve written them. Kim Gordon, who is a musician and was a member of rock band Sonic Youth, suggested how it is “good to be open to opportunity and possibility – and to the idea that having a career doesn’t mean doing one thing for your whole life.” I think that it is an important lesson for all of us, but particularly Milennials and young adults who are coming into a new economy of ideas and opportunities. But change can create an underlying anxiety. How did you deal with any fear and anxiety you may have experienced when you made a career switch?

When I would walk toward my boss’s office feeling nervous because I wanted her approval, I told myself that this was good fear and anxiety because it meant I was going outside of my comfort zone – that I was going to learn and grow. For the fear and anxiety that felt less useful, I talked to trusted colleagues and close friends. That helped. I went running or swimming to try to stay calm and level headed. And I pursued something outside of work but connected to it – which was developing this book! It felt good to have a creative project that was my own.

Q: What’s been the biggest surprise about sending a book into the world?

I think the biggest surprise is that while complimentary reviews in official publications have felt good, it’s also pretty amazing to hear from readers – people at my job, others – about what they got from this book, and so satisfying to hear that it’s been helpful to people.

And now, for some fun questions…

I have not read the book, but the idea of making a mistake and learning from it is refreshing rather than reading the countless ways women can and should achieve perfection while balancing and juggling multiple balls, and “have it all,” whatever “having it all” means. From the time Betty Friedan labeled “the problem that has no name” the feminine mystique, educated women have been throwing in the sponge, questioning how their education fits them for homemaking and motherhood, and what is the highest use of themselves.

I have gone through a positive transformation after reading this book. In the preface, it is mentioned that most women with high ranking positions are usually sharing in detail their true mistakes in getting to the top. As a person who is just starting out, I feel connected to the stories. It a good read. I love how most of the contributors mentioned that women tend to be apolagetic at the workplace. They then share secrets on how to overcome. Each contributor comes from a variety of bavkground with so many different advice. Its almost like a women career development conference blended and made into a book. Dear Jessica/Mrs Bacal if you are reading this comment,thank you so much.